HONOLULU — Hawaii authorities may have been violating their own state law for years by issuing commercial fishing licenses to thousands of foreign workers who were refused entry into the country, The Associated Press has found.

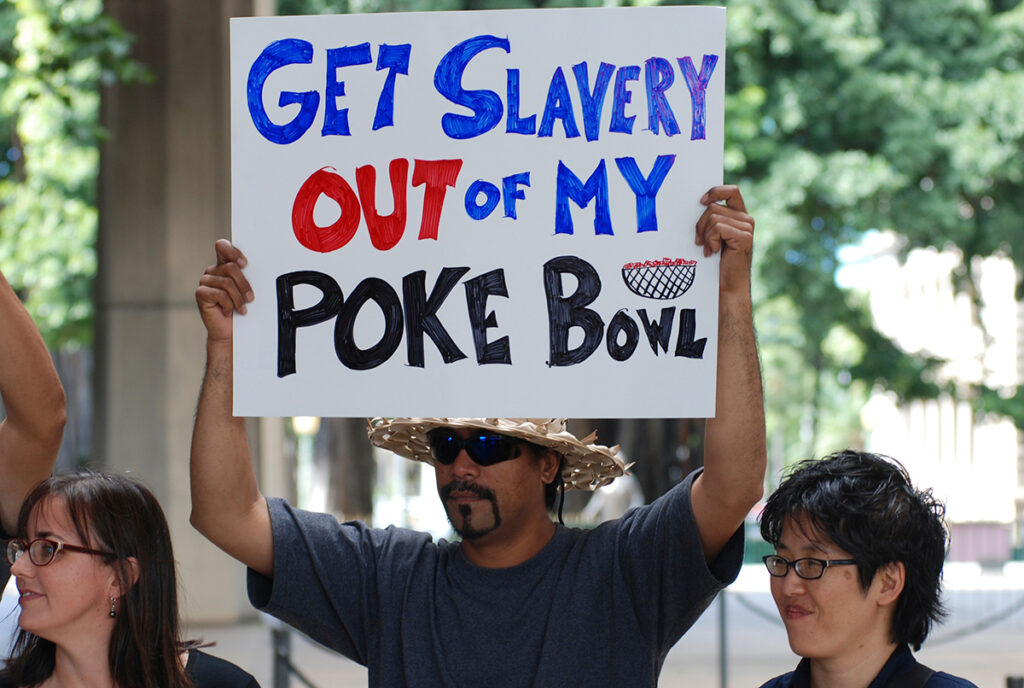

About 700 of these men are currently confined to vessels in Honolulu without visas, some making less than $1 an hour. They work without most basic labor protections just a few miles from Waikiki’s white sand beaches, catching premium tuna and swordfish sold at some of America’s most upscale grocery stores, hotels and restaurants.

The AP found that under state law, these workers — who make up most of the crew in a fleet catching $110 million worth of seafood annually — may not be allowed to fish at all.

A recent industry-sponsored assessment of crew members’ treatment and living conditions found no human trafficking, but raised concerns that workers could be vulnerable to exploitation and said they have little recourse about paying fees or incurring debt in order to hold their jobs.

“There exists no system of grievance mechanisms for crew to voice concerns over pay,” according to the report.

In this unique fishing arrangement facilitated by both federal and state officials, Hawaii’s boat owners pay brokers up to $10,000 to bring each crew member from impoverished Southeast Asian and Pacific island nations. The men aren’t allowed to arrive at Honolulu’s airport because they lack visas, so they are instead flown to other countries and put on U.S.-owned fishing boats for long sails back to Hawaii.

Before the men start working, they need a state commercial fishing license. In order to get it, Hawaii requires that they must be “lawfully admitted” to the U.S.

Here’s the hitch: When they arrive, they are met at the dock by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents who ban them from entering the country by stamping “refused” on their landing permits, which voids them. So instead of being “lawfully admitted,” they are now barred by law from setting foot on U.S. soil.

“Try taking a check to your bank that says ‘void’ on it and telling them, ‘Oh, but they wrote the check to me,’” said Hawaii attorney Lance Collins, who advocates for the workers.

Nonetheless, a written opinion by Hawaii Attorney General Douglas Chin said the Department of Land and Natural Resources provides the landing permits as proof the fishermen are “lawfully admitted.”

U.S. Customs sees it differently.

“NO. They cannot be admitted,” spokesman Frank Falcon wrote in an email, adding that the stamp means they can’t even enter the U.S. temporarily. In rare cases, including medical emergencies, Customs can parole the men to go ashore.

Foreign crews on boats and aircraft, including cruise ship workers and flight attendants, fill out landing permits when they arrive in the U.S. Customs takes those applications and decides whether to allow each individual to temporarily enter the country. When landing permits are stamped refused, that serves as proof that authorities have been alerted that foreigners without visas are on arriving vessels or planes, and triggers an order for captains to detain them on board.

Chin’s office did not respond to AP’s queries about the refusal stamp. However, Land and Natural Resources department spokesman Dan Dennison said in an email that the attorney general advised his agency to continue issuing fishing licenses to the foreign workers despite the fact that Customs says the men are not “lawfully admitted.”

“There exists no system of grievance mechanisms for crew to voice concerns over pay.”

The Hawaii Longline Association, which represents boat owners, says the men are legally hired for legitimate work on the fleet’s 141 active vessels. And while the conditions and pay are often below U.S. standards, the jobs are typically better than the bleak opportunities the men have at home, mostly in the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and the tiny Pacific island of Kiribati.

Under federal law, U.S. citizens must make up 75 percent of the crew on most American commercial fishing boats. An AP investigation last year revealed Hawaii’s fleet relies on a federal loophole allowing the foreign fishermen to work.

In a hearing prompted by the AP report, Land and Natural Resources department administrator Bruce Anderson was asked why he issues commercial fishing licenses to foreign workers who can’t enter the state.

He said the crewman’s landing permit “says in essence that the individual has the right to fish in U.S. waters but cannot step ashore.” He did not mention that all the permits were stamped “refused.”

Democratic state Rep. Kaniela Ing, chairman of the Ocean, Marine Resources and Hawaiian Affairs committee, has queried Chin and other state officials at length about why the men cannot leave their boats.

Ing said state officials failed to disclose the refusal stamp to him when he asked to see the landing permits.

“It always seemed paradoxical that the proof of lawful entry was a landing form, but the crew members weren’t allowed to land or leave the boat,” he said, after the AP told him about the stamp. “We just didn’t have the smoking gun evidence to point to why, and now we do.”

Critics say the fishing licenses could be just one of several ways the state is breaking its own laws:

—The lowest-paid fishermen have contracts promising $300 a month, well below the state’s wage minimums. The Labor Department says it doesn’t intervene because the workers fall under federal, not state, jurisdiction. But department head Linda Chu Takayama also said she’s awaiting further legal guidance.

— Chin, the attorney general, said in his written opinion that employers in Hawaii typically cannot withhold wages, but some fishermen told the AP they are paid only after returning home when their one- or two-year contracts end.

— Chin said telling consumers “that fish had been caught by local fishermen” may violate the state’s deceptive practice laws if misinformation likely affects their shopping choices. The Hawaii Seafood Council claims the catch is “produced by Hawaii’s hard-working fishermen.” Council Program Manager John Kaneko did not respond to the AP.

Federal law also is in question: U.S. Customs requires captains to detain the men on board and hold their passports because they are banned from entering the country. That potentially goes against U.S. human-trafficking laws saying bosses who possess workers’ identification documents can face up to five years in prison.

The foreign fishermen’s catch is sold everywhere from Costco to Sam’s Club and upscale restaurants across the U.S., including Trump International Hotel Waikiki. Whole Foods announced it would suspend buying seafood from the fleet after the AP’s initial report, while Costco says it is monitoring the situation. The Trump hotel and Wal-Mart, which owns Sam’s Club, did not provide an immediate response.

The story also exposed dangerous, unsanitary conditions and at least two instances of human trafficking. It prompted new commitments from boat owners to protect the crew members’ welfare.

After a follow-up briefing on Capitol Hill, several members of Congress expressed “grave concerns” about working conditions in a letter to the Coast Guard and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Hawaii Seafood Council’s survey of 207 fishermen identified a series of potential problems, particularly involving recruiting and payment of the foreign crew.

Some fishermen had contracts requiring that part of their salaries or identification papers be withheld until they returned home. Others had signed agreements that said they had to pay for replacement workers if they broke their contracts, or faced $5,000 fines for absconding — equivalent to a year’s salary for some.

However, the assessment also found some fishermen had excellent relationships with their captains. All said they were being paid in cash, and none expressed concerns about forced labor or human trafficking.

No one complained about access to food, but the report described one labor agent as saying that she had men on a boat who had not been paid for two months and that she bought groceries for fishermen at times when their boats ran out.

The industry has implemented a new universal crew contract that requires owners to pay all recruiting fees and gives the fishermen their salaries within four days of landing. A draft Code of Conduct seeks to safeguard workers’ rights.

But there are no wage minimums as initially promised by Hawaii Longline Association president Sean Martin. The Honolulu Fish Auction now does business only with boats whose workers have signed those agreements.

Martin declined to be interviewed, but he and other industry leaders have condemned labor abuses. They have said the workers are happy to have the jobs and typically do not complain, with many renewing their contracts and even recruiting relatives.

Still, little has changed, with foreign crews typically spending three weeks a month at sea, working up to 20 hours a day, usually for far less than American fishermen nationwide, who average $2,500 a month. Their situation has been widely accepted as legal.

The AP investigation is part of an ongoing global look at labor abuses in the fishing industry, stretching from Southeast Asia to America’s own waters.

In 2015, the AP reported on fishermen locked in a cage and others buried under fake names on the remote Indonesian island village of Benjina. Their catch was traced to the United States, leading to more than 2,000 slaves being freed. But thousands more remain trapped worldwide in a murky industry where work takes place far from shore and often without oversight.

In Hawaii, most vessels dock at piers 17 and 38, which are guarded and patrolled, but some go as far as the West Coast. And, although technically not allowed, they do venture onto the piers briefly to socialize and use restrooms.

Last year, Customs said six fishermen were deported after wandering away from their boats in Honolulu, some to visit friends on other vessels, others sneaking away for a drink.

In 2010, two Indonesian fishermen who fled their boat in San Francisco alleging abuse were granted visas as victims of human trafficking and are now suing their former boat owner.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement spokeswoman Virginia Kice said agents checking out a number of leads related to possible human trafficking in the fleet have “identified instances where crew members were contending with less than ideal working conditions,” but found no situations meeting the legal threshold to bring criminal charges.

Federal marine observers, who live with the men for weeks at a time at sea, said some fishermen have good working conditions while others are sometimes mistreated, not given proper health care, provided unclean drinking water and fed bait and rice. Many are forced to use buckets as toilets on board.

Others in the community also have concerns. Uli Kozak, an Indonesian language professor at the University of Hawaii who has long exchanged home-cooked meals for fresh fish, said the workers sometimes ask for vegetables because of shortages on board.

He said some captains have banned men from speaking their native language on boats.

There’s “a lot of verbal abuse, even physical abuse, being slapped in the face,” Kozak said. “I have come across cases where people said, ‘If I had ever known that it would be as bad as this, I would have never taken that job.’”

Follow Martha Mendoza and Margie Mason on Twitter at @mendozamartha and @MargieMasonAP